What individual neurons do. This wiki is most interested in large groupings of neurons, treating them as the unit of discussion.

This page needs more work before it's ready for outside review.

An expert in the topic of this page will wince (at best) while reading it.

structure

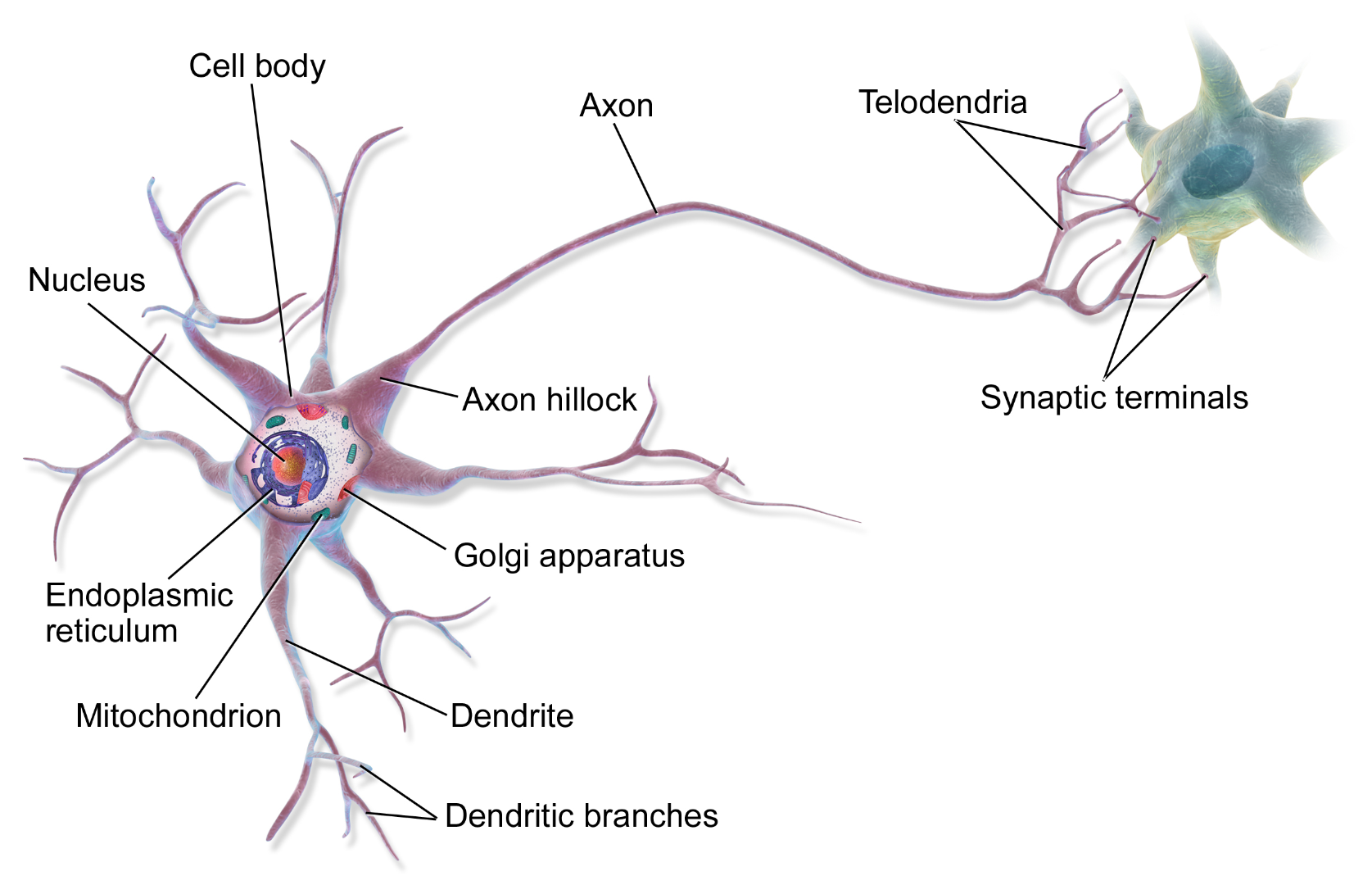

A neuron is a cell that can maintain an electrical charge. Structurally, it's the same as most cells, except it has an *axon* and multiple *dendrites*.

Think of an axon as a long vine leading outward from the neuron. It has a branchy structure and may be up to a meter in length (in humans). Axons carry the neurons pulses (see below) to other neurons.

via Wikimedia Commons ![]() . Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

Dendrites are more like many shrubs rooted on the cell wall. Like the axon, they are branchy, but they do not extend nearly as far. Dendrites receive incoming pulses from other neurons.

The tips of axons come very, very close to multiple neurons' dendrites. We might as well say that each axon tip is connected to a dendrite.

Because axons branch and dendrites accept connections from many axons, each neuron is attached to a vast number of other neurons, around 7000 on average.

(I'm ignoring here, and throughout this wiki, the different kinds of neurons. Some are not, for example, nearly so interconnected. But when it comes to the neurons involved in thinking, it's reasonable to think of all of them as densely interconnected.)

action

When a neuron's interior charge reaches a certain threshold, it produces an electrical pulse that travels down the axon to all that axon's connected dendrites.

So, very roughly speaking, we can think of a neuron as occasionally sending one bit of information to its neighbors.

How does the neuron's stored charge change?

* In response to **pulses received** at the dendrites. Those pulses can add on to the neuron's stored charge or they can reduce it (thus making the neuron less likely to "fire" a pulse to its adjacent neurons).

* As a result of **sending a pulse**. The neuron's charge reverts to its baseline level.

* In some neurons, it just does. Certain neurons, upon reverting to baseline level, begin **autonomously accumulating more charge**. Such neurons pulse at regular intervals and can be used as clocks. (There is no master clock for the whole brain, though, the way there is for a computer.)

see also

The core abstraction – the "atom" upon which I'll build this story – is Self-Reinforcing Networks. Rather than following that, though, best to return to (or start with) One Associationist Theory of Thought.